I had a request to continue posting Fr. Matthias' homilies...so I am honoring that request. Enjoy and God bless your journey!

Readings: Is 45:1-6; 1 Thess 1:1-5; Mt. 22:15-21

Next month we will celebrate the feast of Thanksgiving, one of the most beloved of our American holidays. This day has a diverse history of sources. The most common one takes it back to the Puritans in 1621 and their celebrating their first harvest in their new land. But all the European settlers in America brought some kind of feast celebrating the end of the fall harvest season. Scholars today dispute whether the first thanksgiving feast on American soil took place in Massachusetts, or Virginia or even Florida (with the Spanish explorers).

Religiously, thanksgiving goes back a lot farther in time. The oldest materials in the Old Testament, from the book of Psalms, shows that praise and thanksgiving were the two dominant responses of the ancient Israelites to their God, Jahweh. That was quite unique among all the religions around them. In those other religions people feared their gods, appeased their gods, and then made requests to their gods. Seldom do we find any mention of praise and thanksgiving. But it runs through the whole Psalter of the Old Testament. There were sacrifices of thanksgiving offered to the Lord God, and these were accompanied by people praying the psalms of thanksgiving while a priest was doing the sacrifice. Here’s an example of that: "I praise you, Lord, because you have saved me....You have changed my sadness into a joyful dance...you have taken away my sorrow and surrounded me with joy...Lord, you are my God; I will give you thanks forever." (Ps. 30)

Those same attitudes of praise and thanksgiving carried over into the early Christian communities. All of their literature is characterized by them. I’ve always been impressed by the passage of today’s second reading from Paul’s first letter to the Thessalonians, which is probably the oldest Christian document we possess. I still remember the first time I read it as a novice at St. Meinrad. As novices, we were encouraged to read the Bible, especially the New Testament, during our novitiate year. When I first read those lines, "We give thanks to God always for all of you, remembering you in our prayers..." I just sat there in stunned silence for a while. Wow! I thought. Thanking God for the people who are and were part of my life. I realized how easy it is to take them all for granted. I just started right there to pray for my mother and my father, my two sisters, my teachers in high school and so on. I realized for the first time that to thank God for these people IS to pray.

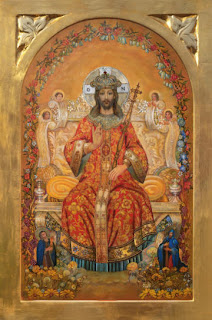

That same attitude of thanksgiving carried on in the whole Christian Church. They called their basic worship service Eucharistia, the Thanksgiving. What we call the mass—they called Eucharistia, the Thanksgiving. What we are doing here today is one big act of giving thanks to God.

It would be good for all of us to call that to mind explicitly and often.

Thanksgiving is, indeed, one of the basic characteristics of Christian spirituality and life. Sometimes it can be very hard to be thankful for our lives. There can be so much illness and such difficult settings in a person’s life that it’s hard for people to be thankful. And that’s understandable. But that’s all the more reason to participate in the Eucharist. There people can join a general setting of thanksgiving and participate in a group setting, when they find it very hard to be thankful on an average day. So we are performing here today a group act of thanksgiving, not just for ourselves but for all the people we know who find it hard to give thanks themselves. Let’s take a moment now and remember them in our hearts.

Today, I celebrate my 50th birthday. If you want to know how my 8th graders celebrated my birthday click on the following links!

Today, I celebrate my 50th birthday. If you want to know how my 8th graders celebrated my birthday click on the following links!